Why data security does not mean data privacy?

Data privacy and data security have become hot-button issue in recent weeks. Facebook, the social networking giant with over 214 million active users in the US and 2.2. billion worldwide is the focus of public scrutiny and ire. It has been reported that profiles of fifty million Facebook users was not just accessed without their consent by a 3rd party developer and then sold to a consulting firm which the data to sway these same users in the 2016 US Presidential elections. Its gets even worse, Facebook knew about this three years ago but did not come clean with a disclosure. Not surprisingly, people feel betrayed by Facebook who they had ‘trusted’ with their data.

So, there is a breach of trust. But, is there a breach in data privacy and/or data security? What do these two terms mean? Information is “secure” when a system correctly enforces the access rights to that information by its users. For example, with proper identification (username and password and optionally a code), you can access your account and no one else can. This is an example of information security and privacy. Information is also “private” when users other than the owner have a ‘read’ access to it as long as this access has been approved and enabled by the owner. Maintaining and enforcing information access to the authorized users is representative of data security. Data privacy is impossible to enforce in a system unless that system is secure, but the reverse is not true. We can understand data privacy and data security and they are entwined yet distinct by using a simple matrix model.

For example, let’s take an example of 3 users of Facebook, John, Jane and Tim. Each of them has permission to read, write and share their own information. Based on the privacy settings in Facebook, they can either allow their friends to read their posts or share and comment on their posts. In additions to their ‘Friends’, Facebook has access to all the contents of each Facebook user. This valuable information is used to create target ‘audiences’. Advertisers pay Facebook for advertising to this audience, its major source of revenue.

Figure 1

| John's Profile+Content | Jane's Profile+Content | Tim's Profile+Content | |

|---|---|---|---|

| John | Read/Write/Share | ||

| Jane | Read/Write/Share | ||

| Tim | Read/Write/Share | ||

| Access to profile and content | Access to profile and content | Access to profile and content |

*User information is shared anonymously with vendors selling consumer product and services for purpose of advertising.

The privacy policy for Facebook is illustrated in Figure 1. Users John, Jane and Tim read/write/share content through their account. In addition, a user grants Facebook authorization to access to their content when the user signs up for the free service (for advertising purposes), but Facebook cannot sell the data directly and does not have the right to grant unauthorized access to user’s data. In this case, it is a very gray line regarding the user’s privacy. Facebook has complete rights on their data. Security is enforced when the privacy policy is applied according to the user’s instructions and knowledge.

Figure 2

| John's Profile+Content | Jane's Profile+Content | Tim's Profile+Content | |

|---|---|---|---|

| John | Read/Write/Share | ||

| Jane | Read/Share | Read/Write/Share | |

| Tim | Read/Share | Read/Write/Share | |

| Access to profile+content+actions | Access to profile+content+actions | Access to profile+content+actions |

A user can enable another user Facebook by becoming a “friend” to view or access their content and profile information. This altered privacy setting is represented in Figure 2. In this setting, John A. has decided to let Jane B. and Tim C. access his profile and information. That results in a change in the security state that Facebook must enforce. The updated security state is reflected in Figure 2, where Jane B. and Tim C. are now authorized to have read access to John A.’s Profile + Info. This is still is secure since the privacy settings of the users are being enforced. Moreover, the information in the system is still ‘private’ because, the privacy settings are being followed.

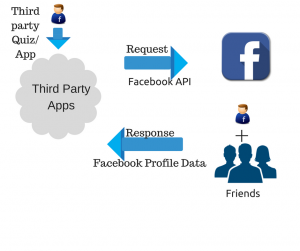

Facebook APIs and breach of trust

In the above scenario, the user is explicitly allowing their Facebook “Friends” to not only read their content but share it as well. There is also an “under-the-table” way of accessing Facebook user data – through Facebook APIs. The Facebook APIs allowed third party software developers to write a program to read and access the data of users who signed up for their program. This also includes other apps who allow their users to login with their Facebook ID. While Facebook terms say they only allow access to the profile of the user who used the program, in actuality they were allowing access to the profile and data associated with all of the friends in their network. The profile and data include attributes like date of birth, location, preferences and more.

This is exactly how the Cambridge Analytica, a UK based company got access to 50 million profiles. They published a quiz ‘mypersonality’ that Facebook users voluntarily answered and shared their profile information with the company. In addition to the 270,000 users who answered the quiz, under the wraps, Facebook provided 50 million users’ data and profile information.

Figure 3.

| John's profile+content | Jane's profile+content | Tim's profile+content | Usage of the 3rd party developer app | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| John | Read/Write/Share | Used the Cambridge Analytica App | ||

| Jane | Read/Share | Read/Write/Share | Did not use the Cambridge Analytica App | |

| Tim | Read/Share | Read/Write/Share | Did not use the Cambridge Analytica App | |

| Access to profile+content | Access to profile+content | Access to profile+content | Cambridge Analytica had a bridge through APIs | |

| Cambridge Analytica app | Access to Profile + Friends profiles | Access to profile | Access to profile |

** Information of users linked to the targeted user, e.g., John A., is accessed by the 3 rd party developer without consent from the linked users (Jane B. & Tim C.), then later sold to a consulting company.

The ability of an owner to authorize who can access their information determines privacy. Control over access rights, which defines privacy, is useless unless the system reliably enforces the access rights. If there is no enforcement, granting and revoking access have no meaning. That is why there can be no privacy without security. On the other hand, Figure 3 shows, Facebook could have reliably enforce the access rights of the users and therefore be considered secure by not providing Jane and Tim’s data to the third party. But, the 3rd party developers were given access to the friends’ profiles as well. Their data is NOT PRIVATE any more. This is a breach of information privacy and breach of trust by Facebook.

The scenarios depicted through Figures 1, 2 and 3 illustrate the difference and relationship between security and privacy. Information is “secure” when a system correctly enforces the access rights provided by the system. Information is “private” only when the owner of the information has control over who can access the owner’s information. This is possible only if the system is secure, but the reverse is not true.

While we need to hold Internet companies responsible for breach of privacy and trust, we should also assess the risks that we are undertaking when we use services of Web apps that are ‘free’ provided we agree to their terms of service. Our personal data is a valuable commodity that is ‘sold’ or used for economic gains by these ‘free’ services. This is the Faustian bargain that we enter when we agree to the ‘free’ Internet services.